Beginning

Members of the 1st Marines (last names Anderson, Taugner, and Reno) pose for a candid moment during a lull in the action.

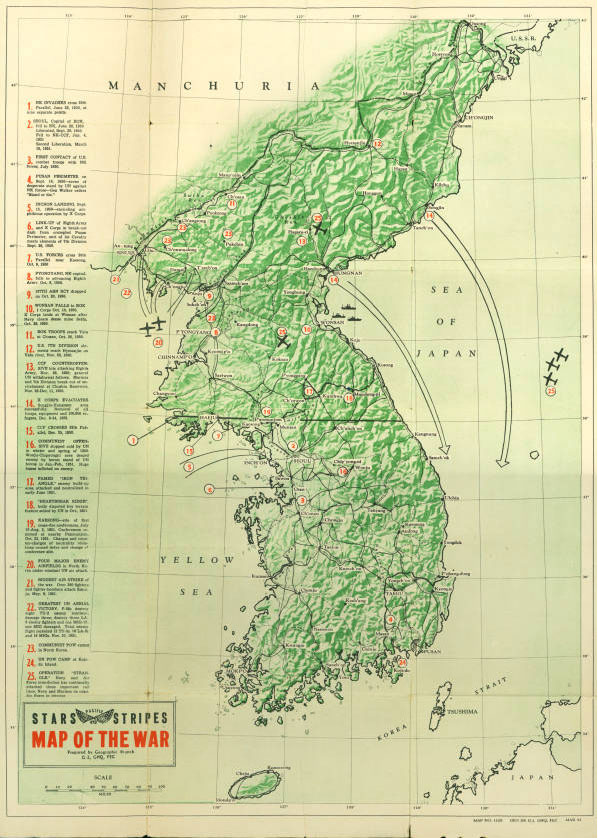

On June 25, 1950, North Korean forces invaded South Korea after failed negotiations for the reunification of the country. Unprepared for this show of force, Seoul, the capital of South Korea, fell in only four days. As the conflict grew, North and South Korea became a Cold War battleground representing the Western World vs. Communism. Officially considered only a "police action" by the United States, the ensuing three-year military conflict included twenty-two countries and resulted in the deaths of an estimated 2 to 4 million military personnel and civilians, including 36,940 American soldiers. Approximately 6,300 Arkansans fought in the Korean War; 461 of those lost their lives.

In response to the hostilities, the United Nations Security Council passed UNSC Resolution 82 on June 27, 1950, promising to defend South Korea. This resolution, passed in the hope of preventing the spread of Communism, marked the first time the United Nations came to the aid of an invaded county. In line with the UN resolution, President Harry Truman authorized the use of American military forces in the conflict. U.S. forces made their first aerial assaults on North Korean targets on June 28. While American units mobilized in Japan, the first U.S. infantry troops, known as Task Force Smith, arrived at Pusan (Busan), South Korea, on July 1, 1950. Outnumbered and unprepared for the organized and heavily armed opposition, Task Force Smith was overrun by the North Korean People's Army (NKPA) and retreated with heavy injury and loss.

The majority of these early battles ended in defeat for the U.S. and UN forces as American casualties reached 6,000 during the first month alone. Expecting to meet North Korean forces that would surrender with only a minor show of strength, the allied forces found themselves disadvantaged to the better trained, organized, and equipped NKPA. Pushed back into the southeastern corner of the Korean peninsula, allied forces successfully defended the "Pusan Perimeter" from North Korean advances while strengthening their forces through more equipment and increased manpower.

Breakout

Seoul, the capital of South Korea, changed hands four times during the first year of the war.

On September 15, 1950, the UN offensive began with a massive landing at Inchon followed by the liberation of Seoul on September 29. The landing at Inchon, a daring offensive envisioned by General Douglas MacArthur, included the First Marine Division, the Army's Seventh Infantry Division, and South Korean units. A successful outcome at Inchon allowed allied forces to move in behind the NKPA at the Pusan Perimeter and on toward Seoul. In conjunction with the Inchon landing, UN forces pushed past the Pusan Perimeter, forcing a general North Korean retreat.

On October 1, 1950, South Korean troops crossed the 38th Parallel and entered North Korea on the offensive followed by U.S. forces six days later. As a group of U.S. forces known as X Corps sailed to the east coast of the Korean peninsula, the 8th Army pushed north and captured Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, on October 19, 1950. South Korean forces began to battle with a new threat, the Chinese People's Liberation Army (also Communist China Forces or CCF), on October 25, but General MacArthur largely dismissed these events as inconsequential until the 8th Army was attacked and forced into retreat by Chinese forces near the end of November.

Retreat

Soldiers from the 1st Cavalry Division pause to rest and collect themselves on the retreat from North Korea following the entry of Chinese communists into the war.

Overwhelmed by the sheer manpower of the Chinese military and now battling the harsh winter weather, American forces were hampered by their separation. UN forces, including the First Marine Division, made a miraculous escape over mountainous terrain to be evacuated by sea after being surrounded in the Chosin (Changjin) Reservoir. Unable to withstand the attacks from the Chinese, allied forces retreated back into South Korea, losing both Seoul and Inchon by January 1951.

The winter of 1950-1951 proved to be costly for both sides of the conflict. Although the Chinese had succeeded in forcing the retreat of UN forces, the human cost of the offensive left them unable to withstand onslaughts as UN forces slowly pushed back toward the 38th Parallel. As the conflict began to stabilize largely where it had started a year before, General MacArthur was removed from his post in April 1951 and replaced with General Matthew B. Ridgeway. Truce talks began on July 10, 1951, followed by an agreement on the 38th Parallel as the line of demarcation on November 21. These talks did not halt the conflict. Fighting continued, largely contained in the mountains surrounding the Parallel, for two additional years as each side sought to strengthen and maintain its position.

Stalemate

The signs of fatigue are clearly evident in the posture of these battle weary soldiers.

Several intense battles mark these two years of stalemate "hill-fighting." The Battle of Heartbreak Ridge, from mid-September to October 15, 1951, took place in an area known as the "Punchbowl." Attempts to take this ridge began with an aerial attack on the well-entrenched North Korean forces, followed by an assault up the steep sides of the hill by waiting troops with heavy artillery support. The NKPA lost Heartbreak Ridge, but the high casuality rate on both sides—3,700 UN troops alone—and the development of heavily fortified, nearly impregnable defense lines discouraged the future use of such large-scale offensives. UN and North Korean forces instead began a series of limited raids, probes, and small-scale offensive attacks that continued through the peace talks.

Just as in early battles, territory changed hands many times during the latter years of the war. The battle for Pork Chop Hill lasted longer than any other single battle in Korea. UN forces suffered a high casuality rate fighting for control of the tactically unnecessary Pork Chop Hill, working against wave after wave of reinforced Chinese troops. The battle began in June 1952 in an effort to secure the dozen hills comprising the high ground in front of the U.S. main line of resistance, with the most violent and intense fighting occurring in April 1953. During one four-day period, U.S. forces won and lost the hill two times. When the cost of defending Pork Chop became too much, it was evacuated by the U.S. and left to the Chinese forces.

Territory won during these hill battles was not of high military importance or tactical significance, but it provided each side with bargaining chips to bring to the negotiation table, a tighter hold on their positions surrounding the 38th Parallel and, perhaps most importantly, a psychological win over their enemies. An end to the hostilities came with the signing of an armistice by the United States, North Korea, and China on July 27, 1953. Notably, a peace treaty between North and South Korea has never been signed.

Map of Korea (1952)